Last Friday evening, I met my friend Debbie for dinner. We met through Girl Scouts when we were kids, and have been friends ever since. Her little niece--almost 3 years old--was with her. We had just been seated on the patio when tornado sirens began to wail. My friend and I were working hard to ignore the warnings, along with all the other diners. Only our little friend mentioned the elephant in the room: "It's noisy!" she told the waitress. We didn't want to interrupt our outing; it isn't often I get to spend an evening with such a charmer.

When I got home, I turned on the TV and realized how irresponsible we had been. Local weather news had preempted all other programming for hours, and I switched it on just as Mike Roberts pointed to the radar map, right where my sister and brother-in-law live, and announced, "This is a debris cloud."

It's estimated that 5 tornadoes hit the St. Louis area, ranging up to F4. It it a miracle that no one was killed? Or is it because of the hard work of meteorologists, the saturation coverage of weather, and the county's emergency services? Probably all of these. My sister took the photo above, as well as these. Luckily, their home was not damaged.

I heard the tornado sirens, and was foolish enough to them, but it could have been much worse without warnings. On January 24, 1967, my mom drove me through a terrible storm to a scout meeting. Shortly before the meeting was over, Debbie's mom came down the steps. She was soaked, her coat was muddy, and we immediately went silent. She told us there had been a tornado, and that she didn't see how people could have survived in some of the homes she'd seen. We all ran up to the parking lot which overlooked the subdivisions. All was dark. Was the power out? Or were the homes really gone? At that moment, we didn't know. Three people died in that tornado, and hundreds were injured, included 2 of our friends who hadn't made it to the meeting. There had been no warning, other than a prediction of storms. Prior to last week, the ’67 storm was the last F4 to hit the Saint Louis area.

Many times my mom has told us the story of the tornadoes in 1896 that hit St. Louis and East St. Louis. Her uncle George was missing after the storm, and his brother Art went out in the rain to look through the rubble. He found George, still alive, buried under the bricks of the building where he worked. George survived grotesque injuries, but Art died of pneumonia soon after. The storm of 1896 killed 255; the third deadliest in US history.

So, yes, I do know better. Next time I'll take a flashlight and the dog and head for the basement. Scout's honor!

Adventures in a wildlife garden, and the native plants, birds, butterflies, and bugs we love!

Nature stories from the border of the Missouri Ozarks.

Wednesday, April 27, 2011

Friday, April 22, 2011

Happy Earth Day, Horace!

I was glad that Lisa, over at A Walk in our Garden, invited me to participate in the Earth Day Reading Project this week. Sponsored by Sage Butterfly's blog, the idea is to talk about 3 books that have inspired you to "live green." There are lots of books about nature that I love and I'll stretch the meaning of "living green" to include them, since for me a love of nature and taking steps to protect it go hand in hand. The first book I will mention is one I read in 8th grade, Camping and Woodcraft: A Handbook for Vacation Campers and for Travelers in the Wilderness, by Horace Kephart (available free from Google books). Kephart was born in 1862; this title was published in 1917. I found it in my local public library.

I was fascinated by his illustrations of various types of shelter, each with a romantic name like "Hudson Bay tent," and "tomahawk shelter." I couldn't wait to follow his instructions for assembling a bed roll for my next camping trip. He quotes a "southern Indian's" advice on building a fire that won't waste wood (Vol. 1, page 232); something I applied each time we camped. There are many things that distinguish Kephart's book from other camping books--his abundant opinions, his instructions for lost arts, his obvious love for the land and the people who lived their lives immersed in it.

Camping and Woodcraft is an 800+ page, two-volume work. Why would a 12-year-old choose this ancient tome? Honestly, there were few other camping books available to me in the mid-1960s. (Today, the St. Louis County Library system lists 164 books on the subject--still low for a system that holds about 1.4 million books.) Unfortunately, Kephart's books are no longer part of the collection. I'm pretty sure I skipped over the chapter titled "Trophies--Pelts and Rawhide," but I checked the book out several times and eventually read everything else.

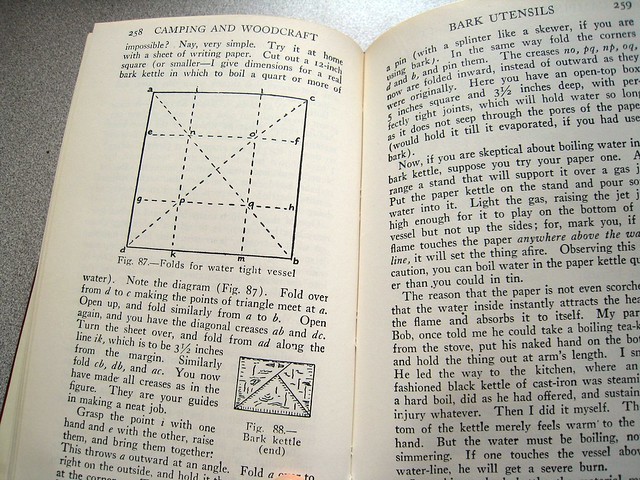

The best material is in Vol. II, Woodcraft: splitting a log, building a "masked camp," bee-hunting, "How to Walk," and cabin building. I tried his instructions--pictured above--for "Boiling water in a bark kettle" (Vol. 2, p. 257). Not having access to birch bark in my area, I constructed it from paper. It actually worked! Not only is the paper kettle watertight, and you cook with it and the paper doesn't burn (usually). I tried some recipes too, including "ash cake," but that wasn't exactly a hit with my scout troop. I'd stay away from the sassafras tea too.

Happy Earth Day, Horace! Maybe some other folks out there in the blogosphere would like to participate in this 3-book tribute. Check out the description of the meme! The rest of my book list will have to wait for a later post.

I was fascinated by his illustrations of various types of shelter, each with a romantic name like "Hudson Bay tent," and "tomahawk shelter." I couldn't wait to follow his instructions for assembling a bed roll for my next camping trip. He quotes a "southern Indian's" advice on building a fire that won't waste wood (Vol. 1, page 232); something I applied each time we camped. There are many things that distinguish Kephart's book from other camping books--his abundant opinions, his instructions for lost arts, his obvious love for the land and the people who lived their lives immersed in it.

Camping and Woodcraft is an 800+ page, two-volume work. Why would a 12-year-old choose this ancient tome? Honestly, there were few other camping books available to me in the mid-1960s. (Today, the St. Louis County Library system lists 164 books on the subject--still low for a system that holds about 1.4 million books.) Unfortunately, Kephart's books are no longer part of the collection. I'm pretty sure I skipped over the chapter titled "Trophies--Pelts and Rawhide," but I checked the book out several times and eventually read everything else.

The best material is in Vol. II, Woodcraft: splitting a log, building a "masked camp," bee-hunting, "How to Walk," and cabin building. I tried his instructions--pictured above--for "Boiling water in a bark kettle" (Vol. 2, p. 257). Not having access to birch bark in my area, I constructed it from paper. It actually worked! Not only is the paper kettle watertight, and you cook with it and the paper doesn't burn (usually). I tried some recipes too, including "ash cake," but that wasn't exactly a hit with my scout troop. I'd stay away from the sassafras tea too.

I had to wait till the age of Wikipedia to find out more about the author. Most of Kephart's writing is about Appalachia, including the area that later became Great Smokey Mountain National Park, so I assumed he had always lived in that area. Episode 4 of Ken Burns' National Parks covers his contribution to the park and the Appalachian Trail. I was surprised to learn that he had a local connection: he directed the St. Louis Mercantile Library for 13 years. The Mercantile is a private library, established in 1846. I was a member of the library when it was located downtown. Now on the campus of University of Missouri-St. Louis, it's the oldest library still active in the US.

I puzzled over his dedication for a long time: “To the shade of Nessmuk in the Happy Hunting Ground.” Nessmuk (George Sears) and Kephart both wrote for Field and Stream and both were obsessed with wilderness. Born in 1821, Nessmuk is another throw-back who regarded progress as a very mixed blessing. It took a lot longer to run down Nessmuk's writings (now also available free from Gutenberg.org).

Some of Kephart's projects would no longer be considered "green," such as marking a trail with a hatchet and building a bed with fresh pine boughs nightly, but his enthusiasm for living simply, surrounded by forests, rocks, and sky make it worth reading even in the 21st Century.

I puzzled over his dedication for a long time: “To the shade of Nessmuk in the Happy Hunting Ground.” Nessmuk (George Sears) and Kephart both wrote for Field and Stream and both were obsessed with wilderness. Born in 1821, Nessmuk is another throw-back who regarded progress as a very mixed blessing. It took a lot longer to run down Nessmuk's writings (now also available free from Gutenberg.org).

Some of Kephart's projects would no longer be considered "green," such as marking a trail with a hatchet and building a bed with fresh pine boughs nightly, but his enthusiasm for living simply, surrounded by forests, rocks, and sky make it worth reading even in the 21st Century.

Happy Earth Day, Horace! Maybe some other folks out there in the blogosphere would like to participate in this 3-book tribute. Check out the description of the meme! The rest of my book list will have to wait for a later post.

Tuesday, April 19, 2011

Red Hot Sally Rides Again!

Josey—my long-haired dachshund—and I stepped out the backyard at dusk this evening, just ahead of a huge storm. I bought a few salvias that were already in full bloom, and I wanted to be sure that the predicted hail didn't grind their bones to make its bread. I'm not really very fond of Salvia splendens and its varieties ('Red Hot Poker,' Red Hot Sally,' etc.) Actually, I probably would love it except that I've seen it too often at gas stations and convenience stores. This plant reminds me of a song that I liked till they french-fried it on the radio a million times a day. Please nominate your own "song that gets too much airtime" in comments below. Or plant.

I always get a few quart or two-quart sized containers of red salvia because hummingbirds love them and there's not much else in bloom for early birds. Lanny Chambers at Hummingbirds.net recommends surveyor's tape fluttering from your feeders to bring in the hummers (see my review of his site). I prefer 'Sally.'

Back to nature. Josey and I were out in the back, protecting the Salvias, as I said, when I spotted a large insect in flight. The twilight and impending storm made it impossible to see much detail and for once, I hadn't brought my binoculars with me. Yet it seemed too early for an insect this large to be flying through the yard. Then I saw its silhouette pitch up, in a very non-insect-like flight, and drop onto a twig. My first hummingbird of 2011!

Thanks to *~Dawn~* for licensing her fascinating photo with Creative Commons!

I always get a few quart or two-quart sized containers of red salvia because hummingbirds love them and there's not much else in bloom for early birds. Lanny Chambers at Hummingbirds.net recommends surveyor's tape fluttering from your feeders to bring in the hummers (see my review of his site). I prefer 'Sally.'

Back to nature. Josey and I were out in the back, protecting the Salvias, as I said, when I spotted a large insect in flight. The twilight and impending storm made it impossible to see much detail and for once, I hadn't brought my binoculars with me. Yet it seemed too early for an insect this large to be flying through the yard. Then I saw its silhouette pitch up, in a very non-insect-like flight, and drop onto a twig. My first hummingbird of 2011!

Thanks to *~Dawn~* for licensing her fascinating photo with Creative Commons!

Sunday, April 17, 2011

Golden Currant and Friends

Gardeners with small yards have to prioritize, especially if, like myself, you're a plant collector masquerading as a gardener. Here are some of the questions I ask about a plant before squeezing it in:

Is this plant…

The blooms have the tubular shape typical of hummingbird-pollinated flowers. Stokes Hummingbird Book (Don & Lillian Stokes, 1989) has a concise summary of the characteristics of the plants in this "exclusive club":

Let's see… Golden Currant has a tube-shaped bloom, which—in the interest of bringing you the facts—I munched. It was a little sweet, but then, it's a little flower. The flowers are deep yellow, though as the bloom matures, the tips of the corolla show rusty red. On my bushes, the most of the flowers point upward. The petals are tiny. The blooms are wonderfully fragrant. Color me confused. Which pollinator is the plant trying to attract?

Hummingbird Gardens: Attracting Nature's Jewels to Your Backyard (Newfield and Nielsen, 1996) recommends several species of Ribes, including R. odoratum as hummingbird plants, in the chapters on western gardens. I even found this photo of an Anna's Hummingbird visiting currant blooms in California.

I have not seen a hummer at my currant bushes, but I don't usually see them this early in the season. I have seen lots of bees though. I grabbed my close-focus binoculars—the ones I use for butterfly watching—and had a chance to observe the bees closely. Because they have shiny black abdomens, I judged them to be Eastern Carpenter Bees. Some were males with yellow mouth parts that give them a comic, bucktoothed expression. I couldn't really tell what they were doing inside the flower, but carpenter bees are long-tongued, and should be capable of reaching the base of the bloom to lap up the nectar.

Golden Currant's natural range in my state, according to Shrubs and Woody Vines of Missouri (Kurz, 1997), includes only 4 counties: Shannon, Barry, Stone, and Taney. All of these are deep in the Ozarks, and feature dolomite or limestone glades and bluffs. Some sources call it Ribes aureum var. villosum, but list Ribes odoratum as a western species. Searching for R. odoratum often redirects to R. aureum, so I don't know if there is a difference in distribution across the continent, or just name confusion because of a change in botanical classification.

The USDA's site says that the Kiowa used the plant (whether leaves, fruit, or bark is not given) as a remedy for snake bite. The Kiowa believed this remedy was so effective that snakes were afraid of the currant bush. I haven't seen any rattlers near my bushes either! Many tribes used the fruit in the Native American version of the energy bar, pemmican. I'm hoping my bushes produce fruit this year—you'll need 2 to produce fruit—which I'll be glad to see the birds gobble up.

Is this plant…

- native to my state?

- enticing to hummingbirds?

- inviting to fruit-eating birds?

- attractive to bees and other pollinators?

- found on Missouri glades?

- fragrant?

- easy to cultivate?

- not so tall that it will obscure the view of the garden?

The blooms have the tubular shape typical of hummingbird-pollinated flowers. Stokes Hummingbird Book (Don & Lillian Stokes, 1989) has a concise summary of the characteristics of the plants in this "exclusive club":

- tube or trumpet-shaped blooms that produce nectar at the base of the tube

- flowers are usually red

- blooms point downward

- flowers have small petals, without a "landing platform" for insects

- flowers produce no fragrance

Let's see… Golden Currant has a tube-shaped bloom, which—in the interest of bringing you the facts—I munched. It was a little sweet, but then, it's a little flower. The flowers are deep yellow, though as the bloom matures, the tips of the corolla show rusty red. On my bushes, the most of the flowers point upward. The petals are tiny. The blooms are wonderfully fragrant. Color me confused. Which pollinator is the plant trying to attract?

Hummingbird Gardens: Attracting Nature's Jewels to Your Backyard (Newfield and Nielsen, 1996) recommends several species of Ribes, including R. odoratum as hummingbird plants, in the chapters on western gardens. I even found this photo of an Anna's Hummingbird visiting currant blooms in California.

I have not seen a hummer at my currant bushes, but I don't usually see them this early in the season. I have seen lots of bees though. I grabbed my close-focus binoculars—the ones I use for butterfly watching—and had a chance to observe the bees closely. Because they have shiny black abdomens, I judged them to be Eastern Carpenter Bees. Some were males with yellow mouth parts that give them a comic, bucktoothed expression. I couldn't really tell what they were doing inside the flower, but carpenter bees are long-tongued, and should be capable of reaching the base of the bloom to lap up the nectar.

Golden Currant's natural range in my state, according to Shrubs and Woody Vines of Missouri (Kurz, 1997), includes only 4 counties: Shannon, Barry, Stone, and Taney. All of these are deep in the Ozarks, and feature dolomite or limestone glades and bluffs. Some sources call it Ribes aureum var. villosum, but list Ribes odoratum as a western species. Searching for R. odoratum often redirects to R. aureum, so I don't know if there is a difference in distribution across the continent, or just name confusion because of a change in botanical classification.

The USDA's site says that the Kiowa used the plant (whether leaves, fruit, or bark is not given) as a remedy for snake bite. The Kiowa believed this remedy was so effective that snakes were afraid of the currant bush. I haven't seen any rattlers near my bushes either! Many tribes used the fruit in the Native American version of the energy bar, pemmican. I'm hoping my bushes produce fruit this year—you'll need 2 to produce fruit—which I'll be glad to see the birds gobble up.

Sunday, April 10, 2011

A Walk on the Wild Side

|

| Texas bobcat, photo by Matthew High |

Patricia Lichen's cat! Patricia commented on my previous post about sounds in the night that she wasn't sure what made the strange call

but her cat seemed to!

Her cat was justifiably upset because the call we heard before dawn in the woods of Bentsen State Park was a bobcat (Lynx rufus texensis). Reportedly, bobcats are fairly common in this part of southeastern Texas, near the Rio Grande. According to Wild Mammals of Missouri, Schwartz and Schwartz, 2001, March is the peak of the breeding season in Missouri. This was March 16 in Texas, so it's possible that the Pauraque wasn't the only amorous singer on the prowl.

Bobcats have the widest range of all the wild cats of the Americas; from southern Canada—where they may compete with the larger Canada lynx (Lynx canadensis), down to central Mexico. That bobbed tail usually helps distinguish a bobcat from a feral domestic cat, but a bobcat is also about twice the size of a pet cat: 17-23 inches tall and between 11 and 30 pounds. According to Wikipedia's article, it is absent from most of Missouri, but Wild Mammals of Missouri, other sources and experience disagrees. I saw my first bobcat in Jefferson County, Missouri, crossing a country road at night. Friends in Dent Country tell me they see them on occasion. We didn't get to see this one, but I'm glad we heard him.

Thanks to Matthew High for his great photo of a bobcat seen in west Texas in September.

Tuesday, April 5, 2011

Mysterious Sounds of the Night…

|

| Common Pauraque in Estero Llano Grande State Park, Hidalgo Co. Texas. Photo by David Marjamaa. Used by permission. |

Before dawn on March 16, we arrived at Bentsen-Rio Grande Valley State Park, outside of Mission, Texas. Our trip leader, Bill Rowe, had arranged for us to meet biologist and blogger Mary Gustafson at Bentsen to find the Common Pauraque. David Marjamaa, who took this great photo above, was part of the group too, along with me and five others.

Nightjars are fascinating creatures, loaded with folklore, cryptic coloring, and evocative names. I presume that the name of the family, "Nightjar," comes from the fact that the typical calls of some species "jar the night," in the sense that the voice heard in the night is startling or has a disagreeable effect on the human listener. Of course, that "jar" is in the ear of the listener. I'm most familiar with one of Missouri's nightjars, the Whip-poor-will. Here's a beautiful recording by Lang Elliott. Its song is one of the most beautiful and haunting sounds in nature. A Whip-poor-will can belt out his clear, "whip poor WILL! whip poor WILL!" up to 400 times without a break.

One breezy night in June, deep in the Ozark hills, a Whip-poor-will, perched on the ridge pole of our tent, came dangerously close to breaking that record. Tent-mate and guest blogger, J Bowen suggested solving the problem with a shotgun. I pretty much think that would be jarring in the night too, J!

One breezy night in June, deep in the Ozark hills, a Whip-poor-will, perched on the ridge pole of our tent, came dangerously close to breaking that record. Tent-mate and guest blogger, J Bowen suggested solving the problem with a shotgun. I pretty much think that would be jarring in the night too, J!

But I digress. We are talking about a different nightjar, the Common Pauraque. We walked down the road in the dark, hearing the "Quawk!" of Black-crowned Night-Herons amid the sounds of unfamiliar frogs and insects to me. First we strained to hear a distant Pauraque, then a bird answered, then many more. Mary used her industrial-strength flashlight to find the birds. We saw several near the road, making strange hops and short flights like long-tailed moths. Their eyes reflected the light of the beacon like torches.

No wonder these strange birds of the night have acquired so many tales, superstitions, and names. Their call sounds nothing like the English pronunciation of the name, "pah-RAH-kee." I surmised that it had originated from the Spanish, "¿Para que?"—"What for?" But it really doesn't sound like that either. Arthur Grosset pointed me toward an article from the Auk, 1948, that explains that the Mexican name for this bird in nearby Tamualipas is "Parruaca," pronounced "pahrrr-WAH-cuh," which more closely resembles the call. Evidently the word "Pauraque" is an incorrect English transcription. Pauraque's range just barely makes it into south Texas. It's found along both coasts of Central America, on in to northern South America, south to the northern edge of Argentina. In Central America, it's known as "Caballero de la Noche ("Gentleman of the Night") ; apparently, "el Caballero" is believed to be the Don Juan of birds. Nightjars are members of the family known as Goatsuckers, based on the ancient belief that the birds drank milk from goats. A pretty bizarre myth, but I guess those goats kicked up insects that the birds found tasty, and goat herders, frightened by dark, flying shapes in the night, assumed the worst. The scientific name for the family, Caprimulgidae, means the same thing in Latin. Of course, Spanish for Goatsucker would be Chupacabra, but that's another story.

We heard another sound; one we couldn't identify at the time. Imagine some kind of hoarse, nasal baritone saying, ―Wowwwww! oo Wowww! It sounded a lot like the sound file below. What do you think it is?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)